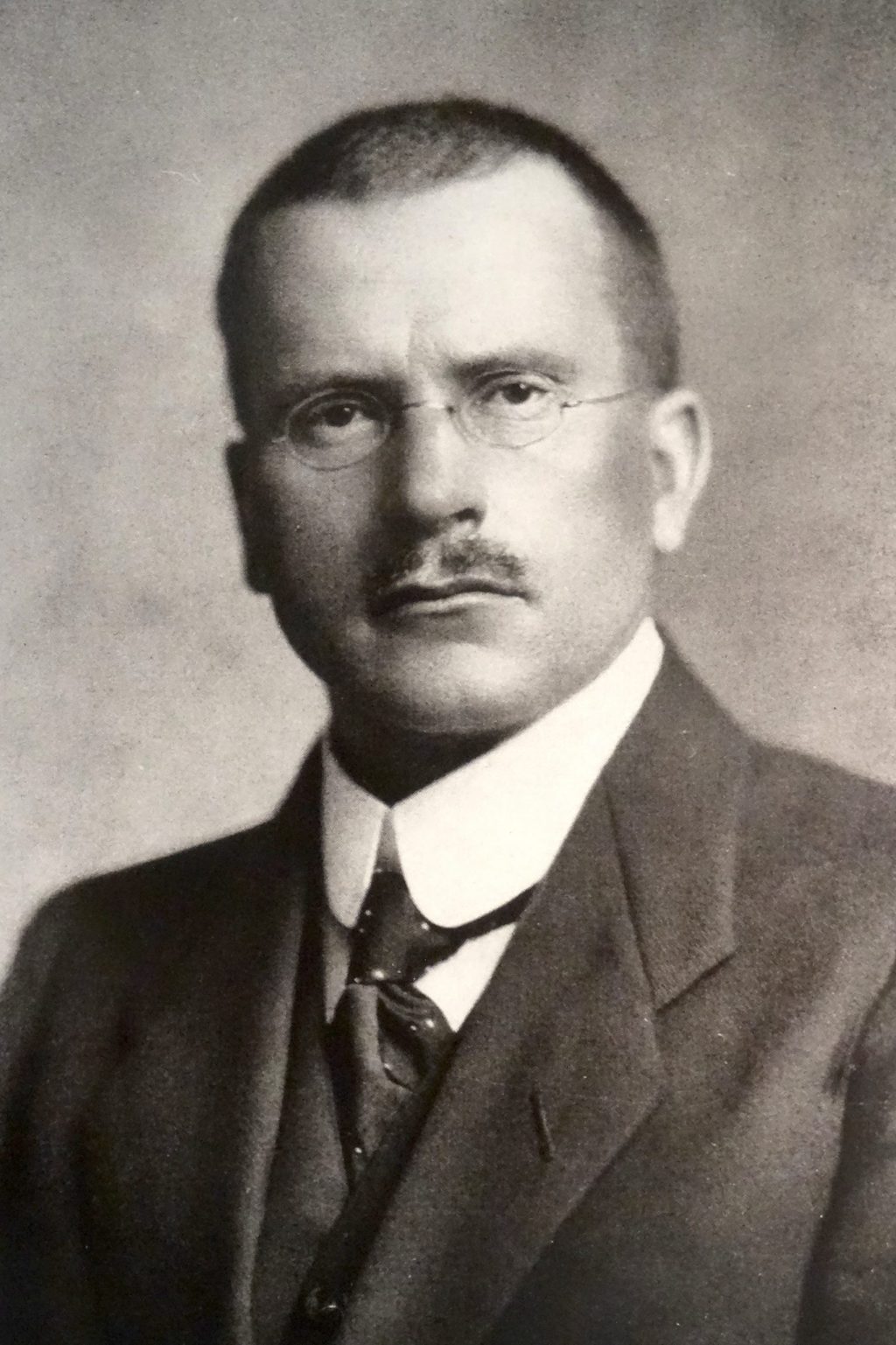

Carl Jung and the Nietzschean Ethic

Carl Jung vastly expands the Nietzschean understanding of ethics in his essay on Good and Evil. At the same time, he evades the question of good and evil itself. He does let it slip near the end, however. Finally, he maintains the tradition set forth by Freud of engaging in philosophy while claiming to not be a philosopher.

The Grand Tradition of Closeted Philosophers

First of all, Carl Jung, in the grand tradition of the most influential psychologists firmly insists that he does not engage in philosophy while engaging in philosophy. He claims that he only takes interest in the empirical aspects of it. This attitude is a vestige of Francis Bacon and Rene Descarte. However, in every other way, it is clear that he has outgrown their influence. For example, he integrates a deep understanding of the concepts of Tao, and Brahma. In that way, he is very much in line with what will later become the Heideggerian tradition.

But even if we were to agree with him that he is being empirical, that choice, in itself, is a philosophical stance. He says he chooses not to engage in philosophy (even as he does so) in order to be able to speak on the subject of good and evil while avoiding having to define his terms; which, ironically, is a perfectly valid philosophical approach, when you are dealing with such complex, normative concepts whose meaning tends to become the center of a kind of normative condensation, rather than being something easily delineated in a nominalistic sort of way.

Jung on Ethical Judgment

Jung does, however, near the end, in response to a question, let his general concept of good and evil be known: “…good and evil are only our judgment in a given situation, or, to put it differently, that certain ‘principles’ have taken possession of our judgment.” This idea is consistent with his treatment of the subject throughout the essay. I consider it to be a stable, consistent conceptual definition for him.

Throughout the essay, he conflates/compares good and evil with more general, broad normative systems of judgment. Like Nietzsche, Jung does not see good and evil as distinct from the ideas people have about good and bad. The main difference seems to be that, while Nietzsche described a qualitative difference between the two normative systems that the majority falsely cling to, Jung simply glosses over that distinction entirely, and takes it for granted that the one is not actually qualitatively distinct from the other, but only seems to be, due to excess of affect.

The Jungian Ethic and the Genesis Trees

Jung, ultimately brings the question back to the religious metaphor of the Genesis trees. In that story, one tree is related to life and God. The other is related to Good and Evil, and death. I believe that he is aware that he is doing this, and is keeping his deeper philosophical insights close to his chest. He only hints at them. For example, in the third paragraph, he mentions the snake from that story.

“‘Ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil,’ whispered the serpent. Only the gods know, not us.”

Illusory Duality

Throughout the essay, he doesn’t so much say, as much as subtly reveal, his understanding of ethical truth; and that is this: the duality of good and evil are, ultimately a useful illusion; one which, through insurmountable challenge and the pall of death, leads us back to the Tree of Life; that center of what is, in which the female nothingness and recession of being into the Tao, and the male assertion of the drawn-into-being-from-the-nothingness God are reunified.

Religion Re-Imagined

Here, of course, I am reading my own religious and philosophical views onto Jung; however, whether he saw this or not, and whether he meant anything like it or not, his essay resonates with it. He even mentions, anecdotally, one of the most effective ways in which God is drawn out into being: “From the East comes the humorous question: ‘Who takes longer to be saved, the man who loves God or the man who hates Him?’ Naturally we expect that the man who hates God takes much longer. But the Indian says: ‘If he loves God, it takes seven years, but if he hates Him only three. For the man who hates God thinks much more about Him.’ What ruthless subtlety!“

Leave a comment